Understanding Fertility

Fertility is described as an individual’s natural ability to successfully conceive a child. There are a number of influencing factors that may affect the chance of achieving a successful pregnancy. To give yourself the best chance of conceiving, it can be useful to understand the fundamentals of reproduction.

Here you will find information about the female reproductive system, the menstrual cycle and how to track it, as well as the role hormones play in fertility.

Reproductive system

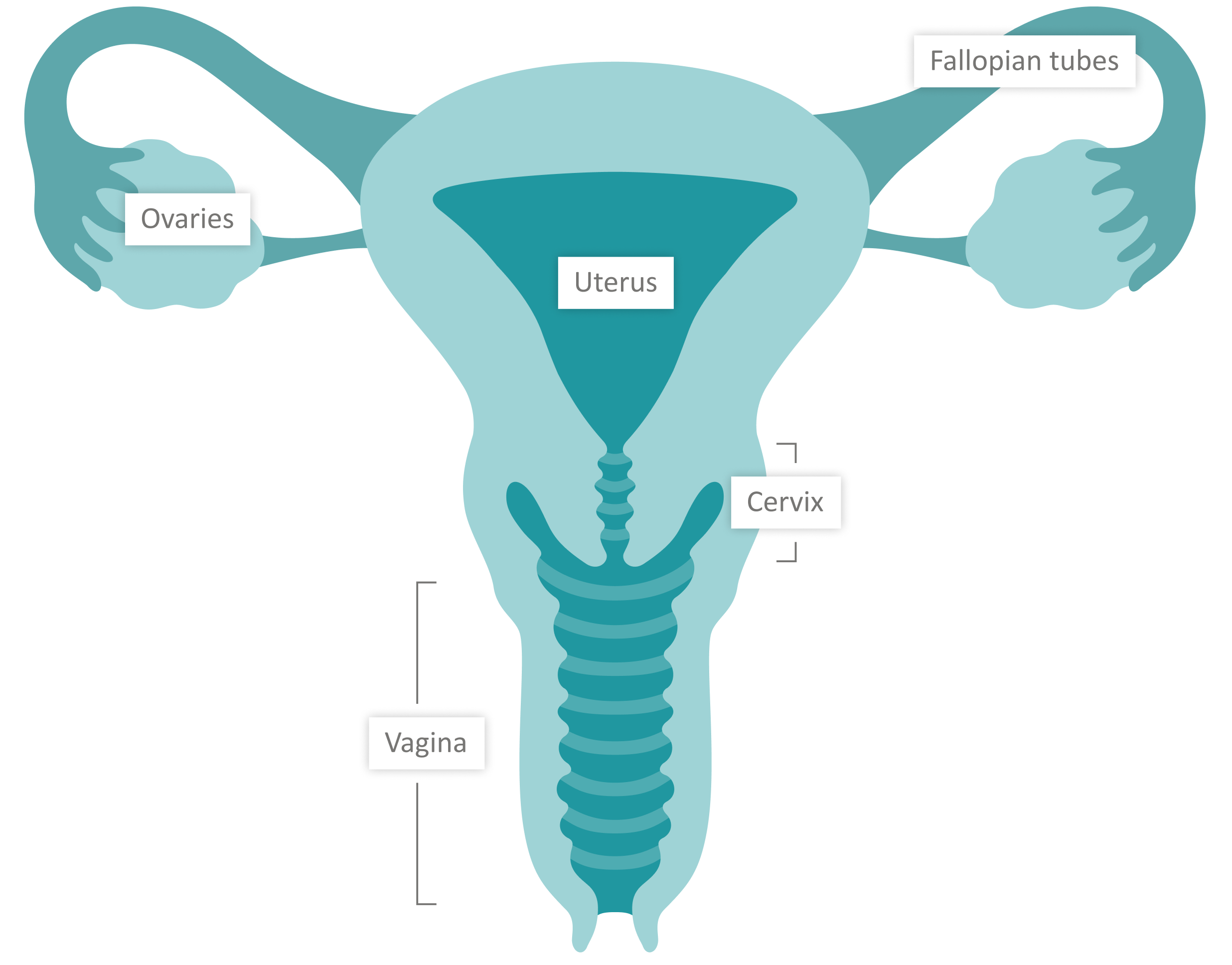

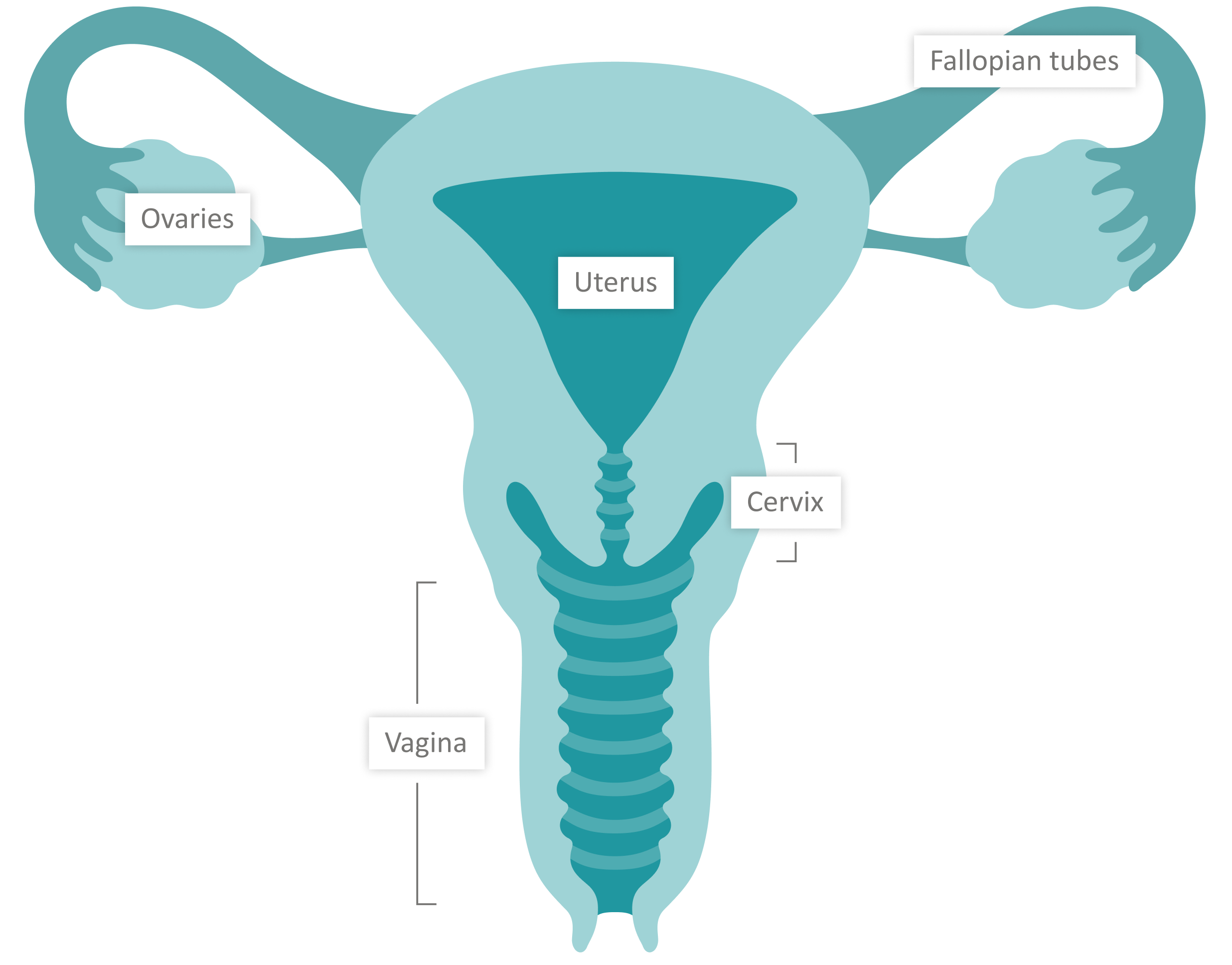

Physiology and function of the female reproductive system

Hover over the image to find out more information

The cervix, also known as the neck of the uterus is a passageway into and out of the uterus. This is the part that widens during childbirth, to allow for the safe passage of the baby. Sperm also needs to travel through the cervix to reach the uterus.

1 of 5 This is a flexible, muscular and tubular organ that extends from the vaginal opening to the cervix (neck of the womb).1 2 of 5 The uterus, or womb, is connected to the fallopian tubes and has the shape of an inverted triangle. A fertilised egg will implant into the endometrium lining (the inner layers of the womb) where it will continue to grow and develop.3,4 3 of 5 This is the organ where the eggs are produced and stored from birth. There are two ovaries in the female body and every month one ovary will release an egg during the ovulation phase of the menstrual cycle. It is also involved in the release of various sex hormones,1 including oestrogen and progesterone.2 4 of 5 The fallopian tubes are tubes that connect the ovaries to the uterus.1 Here the egg, which has been released by the ovaries, may be fertilised by sperm and travel to the uterus to continue its development.3 5 of 5

The cervix, also known as the neck of the uterus is a passageway into and out of the uterus. This is the part that widens during childbirth, to allow for the safe passage of the baby. Sperm also needs to travel through the cervix to reach the uterus.

1 of 5 This is a flexible, muscular and tubular organ that extends from the vaginal opening to the cervix (neck of the womb).1 2 of 5 The uterus, or womb, is connected to the fallopian tubes and has the shape of an inverted triangle. A fertilised egg will implant into the endometrium lining (the inner layers of the womb) where it will continue to grow and develop.3,4 3 of 5 This is the organ where the eggs are produced and stored from birth. There are two ovaries in the female body and every month one ovary will release an egg during the ovulation phase of the menstrual cycle. It is also involved in the release of various sex hormones,1 including oestrogen and progesterone.2 4 of 5 The fallopian tubes are tubes that connect the ovaries to the uterus.1 Here the egg, which has been released by the ovaries, may be fertilised by sperm and travel to the uterus to continue its development.3 5 of 5Adapted from: Elad et al., Physiology 2020.4

The fertility cycle

The luteinizing hormone (LH) surge takes place midway through the cycle (day 15), it marks the end of the

follicular phase and the beginning of the luteal phase. 24-48 hours later, ovulation occurs on average at day 17, although this will vary depending on the length of the cycle.6 Rising oestrogen levels during the follicular phase trigger the brain to release the hormone LH. This causes the mature egg to be released from the ovary and enter the fallopian tube, to be fertilised by sperm.5

This is the second stage of the menstrual cycle. It normally lasts around 14 days and may be accompanied by premenstrual syndrome (PMS) symptoms, such as headaches, mood changes, and food cravings.5

Once the follicle has released the matured egg to be fertilised, it develops into a new structure called the corpus luteum (yellow body). After ovulation, the corpus luteum continues to develop in the ovary at the site of the ruptured follicle that released the mature egg. The corpus luteum is a temporary endocrine structure involved in the production of relatively high levels of progesterone which helps to thicken the lining of the uterus and prepare the woman’s body for the potential implantation of a fertilised egg.5

If fertilisation occurs and the embryo implants into the uterus, the placenta will start producing human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) – the hormone detected by pregnancy tests to indicate a positive result.7 HCG also signals the corpus luteum to continue progesterone secretion, thereby maintaining a thickened uterus lining, providing a favourable environment for the fertilised egg to develop into an embryo.5

From this point on, the corpus luteum is called the corpus luteum of pregnancy, which continues to function until around week 12 of pregnancy. If the egg is not fertilised, the corpus luteum stops secreting progesterone and decays after approximately 10 days. The progesterone drops 2-3 days before the end of the luteal phase and the beginning of menstruation. Oestrogen and progesterone levels decline dramatically, which triggers the beginning of the menstrual phase (i.e., a period).5

Getting pregnant

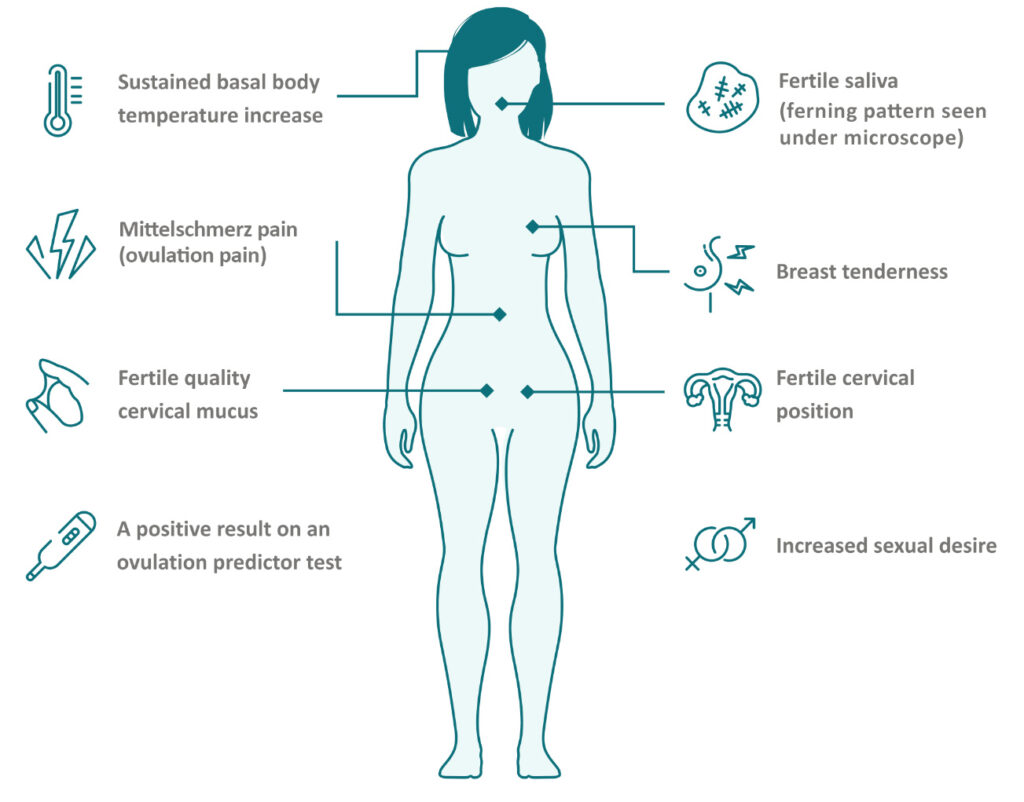

Signs that you are ovulating

When trying for a baby, ovulation is the most important event to consider. Ovulation is the moment the follicle bursts and releases the egg cell into the fallopian tube, where it waits to be fertilised by sperm. It is during the first 24 hours of the luteal phase that a woman is most fertile, and pregnancy is most likely to occur.4

Therefore, becoming familiar with ovulation and when it is likely to occur can help improve the chances of getting pregnant.6 Ovulation test strips are urine-based tests that can be used at home to detect upcoming ovulation. They work by detecting the hormone LH.8 Sometimes they are called OPKs, ovulation predictor kits, or simply ovulation tests.

Some common signs of ovulation are:

Adapted from: Gurevich R, 2020.8

Fertility process

After the egg has been fertilised by a sperm cell, it travels along the fallopian tube to the uterus and continues to divide. The embryo reaches the uterus six days after fertilisation and implants into the thickened endometrium lining where it will continue to grow.9

The outer cells of the embryo will form the placenta9 and produce human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG).7 This is when pregnancy begins and can be detected with a pregnancy test.

Adapted from: Dey SK, J Clin Invest 2010.3

How long does it take to get pregnant?

Whilst some couples will conceive within a year of regular sexual intercourse, for other couples it can take longer. It’s not uncommon for it to take a year or more to become pregnant through natural conception; in fact, 1 in 6 couples have difficulty conceiving within this timeframe.10

Fertility cycle tracking

When trying for a baby, fertility cycle tracking can be a useful way to predict the ovulation period – also known as the fertile window – and therefore when a woman has the highest chance of conceiving. There are a number of period tracker apps available that allow the user to log details of their menstrual cycle every month, such as the timing of menstruation, body temperature, and changes in cervical fluid, which can all be important indicators of ovulation.6 Alternatively, ovulation can be monitored using an ovulation predictor kit. This is an accurate method for determining when ovulation may occur through the measurement of LH in urine, which can indicate when the woman is at their most fertile.6

Fertility hormones

Hormones and the fertility cycle

Hormones play a significant role in the regulation of the reproductive system, from helping the egg to mature, travel to the uterus, and safely implant as an embryo in the uterus lining. If hormone levels are too high or too low, it may have an impact on an individual’s fertility. Read on to learn about the important female fertility hormones and the changes to expect during pregnancy.

Female fertility hormones

Hormones released by the ovaries:

Oestrogen

Progesterone

Hormones released by the brain:

Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH)

Luteinising hormone (LH)

What happens to your hormones during pregnancy?

During pregnancy, the female body will experience various changes – many of them caused by fluctuations in hormone levels:

Changes to human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG):

During pregnancy, a hormone called hCG is produced in abundance by the placenta.7 This is the hormone that pregnancy tests detect in the urine to indicate a positive test.17 It plays an important role in the production of oestrogen23 and progesterone,7 both vital in supporting the growing baby.

Changes to oestrogen

Changes to progesterone

- Rosner J, Samardzic T, Sarao MS. Physiology, Female Reproduction. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537132/ [Last accessed: March 2022].

- Holesh JE, Bass AN, Lord M. Physiology, Ovulation. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441996/ [Last accessed: March 2022].

- Dey SK. How we are born. The Journal of Clinical Investigation 2010;120:952-955. Available at: https://www.jci.org/articles/view/42380 [Last accessed: March 2022].

- Elad D, Jaffa AJ, Grisaru D. Biomechanics of Early Life in the Female Reproductive Tract. Physiology 2020;35:134-143. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32027564/ [Last accessed: June 2022].

- Reed BG, Carr BR. The Normal Menstrual Cycle and the Control of Ovulation. In: Endotext [Internet]. South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc.; 2000-. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279054/ [Last accessed: March 2022].

- Bull JR, Rowland SP, Scherwitzl EB, Scherwitzl R, Danielsson KG, Harper J. Real-world menstrual cycle characteristics of more than 600,000 menstrual cycles. npj Digital Medicine 2019;83. Available at: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41746-019-0152-7#Abs1 [Last accessed: March 2022].

- Montagnana M, Trenti T, Aloe R, Cervellin G, Lippi G. Human chorionic gonadotropin in pregnancy diagnostics. Clinica Chimica Act 2011;412:1515-1520. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0009898111003007 [Last accessed: March 2022].

- Gurevich, R. 8 Signs of Ovulation That Help Detect Your Most Fertile Time. Available at: https://www.verywellfamily.com/signs-of-ovulation-1960281 [Last accessed: March 2022].

- Kim S-M, Kim J-S. A Review of Mechanisms of Implantation. Development & Reproduction 2017;21:351-359. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5769129/ [Last accessed: June 2022].

- Taylor, A. Extent of the problem. BMJ 2003;327:434. Available at: https://www.bmj.com/content/327/7412/434 [Last accessed: March 2022].

- Mihm M, Gangooly S, Muttukrishna S. The normal menstrual cycle in women. Animal Reproductive Science 2011;124:229-236. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0378432010004148 [Last accessed: March 2022].

- Delgado BJ, Lopez-Ojeda W. Estrogen. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538260/ [Last accessed: March 2022].

- Hariri L, Rehman A. Estradiol. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK549797/ [Last accessed: March 2022].

- Cable JK, Grider MH. Physiology, Progesterone. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK558960/ [Last accessed: March 2022].

- Nedresky D, Singh G. Physiology, Luteinizing Hormone. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK539692/ [Last accessed: March 2022].

- Orlowski M, Sarao MS. Physiology, Follicle Stimulating Hormone. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK535442/ [Last accessed: March 2022].

- Thibeault A-AH, Sanderson JT, Vaillancourt C. Serotonin-estrogen interactions: What can we learn from pregnancy? Biochimie 2019;161:88-108. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30946949/ [Last accessed: June 2022].

- Bai J, Qi Q-R, Li Y, Day R, Makhoul J, Magness RR, Chen D-B. Estrogen Receptors and Estrogen-Induced Uterine Vasodilation in Pregnancy. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020;21:4349. Available at: https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/21/12/4349/htm [Last accessed: March 2022].

- Merlino AA, Welsh TN, Tan H, Yi LJ, Cannon V, Mercer BM, Mesiano S. Nuclear Progesterone Receptors in the Human Pregnancy Myometrium: Evidence that Parturition Involves Functional Progesterone Withdrawal Mediated by Increased Expression of Progesterone Receptor-A. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2007;92:1927-1933. Available at: https://academic.oup.com/jcem/article/92/5/1927/2598908?login=true [Last accessed: March 2022].

- Zakar T, Mesiano S. How Does Progesterone Relax the Uterus in Pregnancy? The New England Journal of Medicine 2011;364:972-973. Available at: https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMcibr1100071 [Last accessed: March 2022].

- Szekeres-Bartho J, Halasz M, Palkovics T. Progesterone in pregnancy; receptor-ligand interaction and signaling pathways. Journal of Reproductive Immunology 2009;83:60-64. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0165037809004690 [Last accessed: March 2022].

- Arck P, Hansen PJ, Jericevic BM, Piccinni M-P, Szekeres-Bartho J. Progesterone During Pregnancy: Endocrine–Immune Cross Talk in Mammalian Species and the Role of Stress. American Journal of Reproductive Immunology 2007;58:268-279. Available at: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/j.1600-0897.2007.00512.x?saml_referrer [Last accessed: March 2022].

- Theofanakis C, Drakakis P, Besharat A, Loutradis D. Human Chorionic Gonadotropin: The Pregnancy Hormone and More. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2017;18:1059. Available at: https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/18/5/1059#cite [Last accessed: March 2022].